KRF Clinical Practice Guidelines in Keloid Disorder (KRF Guidelines®) Neck Keloids Version 1.2018

Michael H. Tirgan, MD

SUMMARY

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of neck keloid lesions is based on clinical history as well as clinical appearance of the skin lesion. A biopsy is almost never indicated to establish the diagnosis.

Grouping of neck keloids

For purposes of this Guideline, neck keloid lesions are divided into four types:

- Early-Stage lesions presenting as protruding papules, linear, and nodular lesions (<2 cm – Neck Stage IA).

- Locally Advanced – Organized Patch presenting as conglomeration of papules or linear lesions and formation of keloid patches (2-5 cm – Neck Stage IB).

- Superficially Spreading / Multifocal disease presenting as large areas of neck involvement (> 5 cm in total – Neck Stage IC and above).

- Tumoral disease presenting as bulky tumor mass(es).

- Tumoral – IB (2-5 cm – bulky tumor mass, Neck Stage IB)

- Tumoral – semi-massive (5-10 cm – bulky tumor mass, Neck Stage IC)

- Tumoral – massive (>10 cm – bulky tumor mass, Neck Stage IIA and higher)

Treatment

- Intra-lesional triamcinolone (ILT) is the first-line treatment for all early-stage, papular, and linear lesions (See KRF Guideline – ILT).

- Intra-lesional chemotherapy (ILC) should be considered for all early-stage, papular, and linear lesions that fail to respond to ILT (see KRF Guideline – ILC).

3. Contact-cryotherapy with or without ILT/ILC is the preferred and primary method of destruction for all nodular,

locally advanced and tumoral neck keloid lesions (see KRF Guideline – CRYO).

Rationale for the use of cryotherapy:

a. Cryotherapy is an effective method of treatment for protruding neck keloids.

b. As opposed to surgery, cryotherapy does not cause the worsening of keloids.

c. As opposed to surgery, radiation therapy is unnecessary after cryotherapy [1,3,4].

Cryotherapy should be repeated once every 4-8 weeks, depending on the size of the treated lesions. Once adequate debulking of the keloid is achieved, any remnant keloid tissue must be treated with ILT/ILC to achieve maximum response. All patients should be instructed to examine their neck on a regular basis and return for treatment at the earliest sign of a potential recurrence or development of new lesions.

Treatm ents to avoid

Surgery shall NOT be used in the treatment of neck keloids. Surgical intervention is a known cause for the worsening of neck and other keloids [1, 2], which is also well documented in the cases presented in this Guideline (Figures XXXx).

Surgery may only be considered in cases of massive neck keloids but must be done in coordination with a specialist physician who is familiar with the treatment of keloid disorder and can implement proper adjuvant medical treatments in an attempt to prevent recurrence.

Radiation therapy shall NOT be used in the treatment of neck keloids. This intervention may induce neoplastic transformation of irradiated tissues [3,4].

Lasers shall NOT be used in used in treatment of neck keloids. This intervention may result in the worsening of keloids [5].

Overview

This KRF Guideline was developed with the aim to provide:

- General discussion of neck keloids.

- Natural history of neck keloids.

- Classification system for neck keloids.

- Recommendations for treatment and follow up.

Introduction

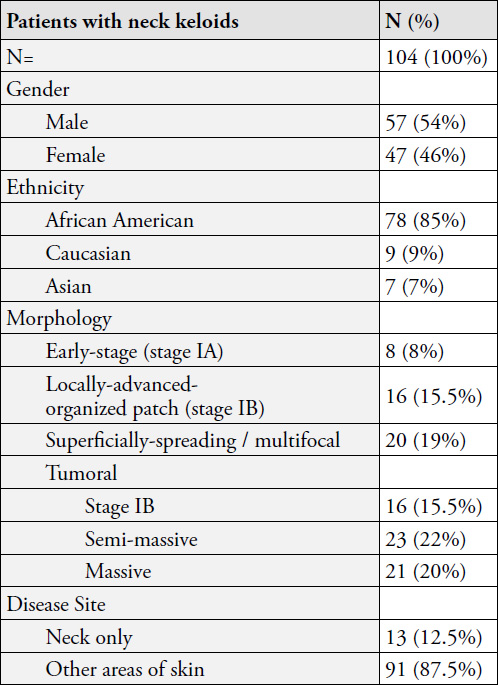

Keloid involvement of the neck skin is fairly uncommon and occurs in approximately 10% of patients with keloid disorder. This pattern of presentation is somewhat race specific. In a recent analysis of data from 1,088 consecutive patients seen by the author is his keloid specialty practice, there were 104 ( 9.6%) patients with neck involvement. Among these patients: 47 (46%) were female and 57 (54%) male; and 78 (85%) were African American, 9 (9%) were Caucasian, and 7 (7%) were Asian.

Clinical presentation of keloid disorder in the neck varies by the ethnic background. The tumoral neck keloids are almost exclusively seen among African Americans. Fifty-seven of the 60 patients who presented with tumoral keloids were African American.

The two most common triggering factors for the formation of neck keloids are acne among Asians and Caucasians and ingrown neck hair among African American men. Proper management of these two factors should be incorporated in the plan of care for all patients.

Involvement of the neck as the only site of keloid disorder is uncommon. Of the 104 cases seen by the author, 91 (87.5%) of these patients had keloid lesion(s) elsewhere on their skin. As with other keloids, the clinical presentation, size, and shape of neck lesions vary from patient to patient. Neck keloids in their early-stages are small and few in number. As time passes, the lesions grow in size and spread to involve larger areas of the neck.

Table 1. Demographics of patients and morphology of neck keloids.

Overall Treatment Strategy

A few basic principles must be considered as we plan to treat any keloid patient, especially those with neck keloids:

- Involvement of the neck is a dynamic process. Over time, the disease will progress in most patients and will result in the enlargement of existing lesions.

- The disease process is multifocal. Quite often patients will form new lesions, either near their original neck keloid(s) or distant from it and in other parts of their skin.

The most important goals of treatment are:

c. To bring the triggering factor(s) under control. Manage acne in all patients and reduce the incidence of ingrown hair in African American men with curly neck hair by trimming hair as opposed to clean shaving.

d. To intervene very early and to bring the lesions under control with a combination of intra-lesional triamcinolone (ILT) / intra-lesional chemotherapy (ILC) and cryotherapy.

e. To avoid surgery in all patients. Surgical removal of neck keloids – a dynamic and multifocal disease – is an inherently flawed approach that exposes patients to the unnecessary risk of developing massive tumoral keloids.

Treatments to avoid

Surgery shall NOT be used to remove neck keloids. As documented in this Guideline, surgical intervention is a known cause for worsening of neck keloids [1, 2].

Radiation therapy shall NOT be used in the treatment of neck keloids. This intervention may induce neoplastic transformation of irradiated tissues [3,4].

Lasers shall NOT be used in used in the treatment of neck keloids. This intervention may result in the worsening of keloids [5].

Early-sta ge Neck Keloids

Neck keloids at their earliest stages appear in three distinct manners:

- Protruding papule(s) that often form in the submental area of neck and are triggered by acne or ingrown neck hair (Figure 1). If left untreated, these lesions can grow to become nodular keloids.

- Linear lesions. If left untreated, these lesions can grow to form thicker linear lesions (Figure 2, 3).

- Nodular lesions. If left untreated, these lesions can grow to form tumoral lesions (Figure 2, 3).

Figure 1. Early-stage papule keloid in a 32-year-old African American female with a 10-year history of keloid disorder, involving her chest and shoulders as well.

Figure 2. Early-stage linear neck keloid in a young Asian male. This lesion was triggered by surgical removal of a mole. A keloid formed at the site of mole removal surgery. The keloid was then excised and the surgical wound was treated with ILT, yet the lesion shown here evolved despite adjuvant interventions. This patient had no other keloids.

Figure 3. Early-stage nodular neck keloid (3a) in a 24-year-old African American male with a four-year history of keloid disorder also involving his face, anterior neck, ears, and chest. This lesion was treated twice with cryotherapy. Figure 3b was taken two years after treatment, showing minimal skin scarring at the site of the treated keloid.

Treatment

There are two distinct goals for treatment of patients with early-stage neck keloids:

- To induce remission.

- To prevent progression / worsening.

It is of utmost importance to manage these early-stage keloids in a manner that prevents the formation of large and tumoral keloids. Both the treating physician and the patient must be cognizant that the disorder is multifocal with a dynamic pathophysiology, and while the triggering factors are still active – with the passage of time – the existing lesions will continue to grow in size. Most patients are destined to develop new lesions, either in the same vicinity or elsewhere on the neck, or other (distant) parts of the skin. It is naïve to think that the keloid process is static, or is limited to only one segment of the neck such that it can be surgically treated. All keloid patients have to be treated in accordance with a long-term treatment and follow-up plan. Patients also need to be adequately educated about their illness and its biology.

ILT injection shall be the first-line treatment for all earlystage papular/linear neck keloid lesions. The lesions must be followed carefully and ILT shall be continued on a regular basis to achieve maximum response. Most lesions do respond to ILT treatment.

It is of equal importance to identify the triggering factor, and in the case of acne, to optimize anti-acne treatment. ILC should be considered early on for all lesions that fail to respond to ILT.

Contact Cryotherapy shall be the first line of treatment for all nodular neck keloids. Any residual keloid tissue that may remain after cryotherapy shall be treated with ILT and/ or ILC. Figure 3 depicts durable treatment results with contact cryotherapy.

Figure 4. Thick linear keloid of neck in a an African American female.

Figure 5. Case Study 1 – A 55-year-old African American female with a 3-centimeter tumoral keloid in anterior neck.

Figure 6. Case Study 1 – Neck keloid immedicably after application of topical cryotherapy (left, the frozen keloid appears white) and six months later (right) after three cycles of cryotherapy.

Progression of the Early-sta ge Neck Keloids

Over time, the untreated early-stage keloid lesions will grow to form nodules, tumors, or to become thicker linear keloids.

Case Study 1

A 55-year-old African American female presented with a 3-centimeter tumoral keloid in her anterior neck (Figure 5). Three years earlier, a small subcutaneous cyst was surgically removed; however, the surgical wound had not healed properly and a keloid formed at that location. The keloid was removed surgically, however, there was a recurrence and the new keloid gradually grew to the size depicted in Figure 5.

This tumoral keloid was treated with contact cryotherapy once every two months. Near total ablation was achieved after three cycles (Figure 6). Four years later, the treated area remains free of recurrence.

For lesions on a path to becoming bulky, the author recommends contact cryotherapy to reduce the bulk of the lesion. Once the mass of the lesion is reduced, treatment with single-agent ILT should be initiated and continued to control the base of the lesion and to prevent recurrence. The frequency of the ILT injections varies from patient to patient, but should be optimized to keep the disease process under control.

ILC should be considered for all patients who fail to respond to single-agent ILT. However, ILT may be combined and be applied in conjunction with cryotherapy for lesions that tend to regrow at a fast pace.

Locally Advanced Neck Keloids

If left untreated, or if treated incorrectly, the keloid process will progress. This is evidenced by continued growth of the neck lesion, an increase in the number of keloid lesions as well as the merger of the existing lesions. Progressive neck disease is often coupled with progression of the disease elsewhere on the skin.

Figure 7. Four examples of locally advanced neck keloids. Treating each one of these patients will require a thoughtfully designed long-term plan of care.

Tumoral Neck Keloids

An untreated or poorly treated early stage neck keloid can eventually grow in size and expand three-dimensionally to form a tumor. For purposes of this Guideline, tumoral neck keloid lesions are divided into three types:

a. Tumoral – IB (2-5 cm – Bulky tumor mass, Neck Stage IB)

b. Tumoral – Semi-Massive (5-10 cm – Bulky tumor mass, Neck Stage IC)

c. Tumoral – Massive (>10 cm – Bulky tumor mass, Neck Stage IIA and above)

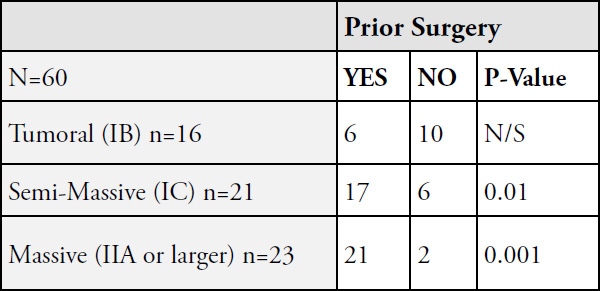

Table 2. Subtypes of tumoral neck keloids

N/S: Not significant

Tumoral neck keloids are almost exclusively seen among African Americans. Among 60 patients with tumoral neck keloids, only three (5%) were non-African American.

Most patients with tumoral keloids have a history of keloid removal surgery. The injury from surgery to either remove a small neck keloid or another pathology is what triggers the formation of tumoral keloids. Therapeutic interventions shall aim at preventing tumoral keloids by avoiding surgery in management of early-stage neck keloids.

Treatment

Cryotherapy is the treatment of choice for all tumoral neck keloids. Surprisingly, these tumors respond well to cryotherapy and can be significantly debulked with one or two courses of cryotherapy. Most patients, however, will need ongoing care and continued treatment to keep the treated keloid under control. ILT and ILC shall be incorporated in management of residual keloid in the base of the debulked keloid.

Figure 8. A 3-centimeter tumoral keloid in anterior neck (left). Significant debulking was achieved after one application of cryotherapy (right, three months later).

Figure 9. A 21-year-old male who presented with a 2 cm anterior neck keloid tumor in May 2011 (9a). The tumor was treated with contact cryotherapy in the same session (9b). Significant debulking was achieved by October 2011 (9c) with cryotherapy alone. Figure 9d depicts durable remission in June 2014.

Figure 10. A 47-year-old male with semi-massive neck keloid that had grown after surgical removal of a smaller keloid.

Figure 11. Same patient as in Figure 10 immediately after application of contact cryotherapy (left – the frozen keloid appears white). Significant debulking was achieved within seven weeks of cryotherapy (right). The remnant of this keloid obviously needs further treatments to achieve better results.

Figure 12. Case Study 2, massive neck keloids at presentation (May 2014). Loss of pigment on the surface of the keloids was secondary to the previously performed spray cryotherapy.

Figure 13. Case Study 2, significant debulking after one course of contact cryotherapy.

Case Study 2

A33-year-old African American male presented in May 2014 for treatment of massive neck keloids (Figure 12). His struggle with keloid disorder had started about 10 years earlier as small lesions appeared on his neck and chest. Over time, he had received intermittent treatments, mostly with ILT. In 2009, he had undergone surgical excision of two keloid lesions from his neck followed by ILT injections. Unfortunately, there was a recurrence at both locations. Spray cryotherapy had been tried once with minimal benefit. In May 2014, both keloids were treated contact cryotherapy once (see KRF Guideline – Cryo). Significant debulking was achieved by July 2014 (Figure 13).

Unfortunately, the patient did not return for follow up until January 2016 (Figure 14). Although there was a recurrence after cryotherapy, it was less bulky than the initial presentation in May 2014. The recurrent keloids were retreated with cryotherapy. Significant debulking was achieved (Figure 15). The base of the keloid was subsequently treated with ILC.

Figure 14. Case Study 2, same patient, January 2016. Recurrent disease after cryotherapy.

Figure 15. Case Study 2, noticeable debulking was achieved with repeat cryotherapy (April 2016).

Figure 16. Case Study 2, recurrent disease after repeat surgery and radiation therapy (January 2018).

Figure 17. Case Study 2, debulking achieved with cryotherapy (March 2018)

After the April 2016 visit, the patient did not return for follow up until January 2018 (Figure 16). Since his last visit, in late 2016 he elected to undergo repeat surgery followed by radiation therapy with hopes and promises of a cure. Unfortunately, this intervention was unsuccessful. The patient returned to the author for further treatment. Both lesions were once again treated with cryotherapy. Figure 17 depicts the results achieved by March 2018.

This case exemplifies the challenges of treating young patients with keloid disorder. Although surgery may at first seem to be a reasonable option for removing a keloid nodule or a small keloid tumor, as is shown here, it often worsens the condition. Furthermore, adjuvant radiation therapy is also not an absolute solution to the prevention of recurrence.

Massive Neck Keloids

Massive neck keloids ( >10 centimeters in diameter, Neck Stage IIA and above) are almost exclusively seen in African Americans (22/23) and mostly those who have undergone surgery to remove a previous, smaller keloid (21/23). These patients all have other keloid lesions elsewhere on their skin (23/23).

Treating these patients is quite challenging as most have already been treated with all available therapeutic interventions. Ideally, these patients need to be treated with a systemic treatment, i.e. a drug that can be safely administered orally or intravenously, in order to bring the disease process under control. Unfortunately, there are no systemic treatments available at this time, with none on the horizon.

Figure 18. Recurrent tumoral neck keloid after two previous surgeries in a 42-year-old African American male.

Figure 19. Recurrence of a neck keloid after surgery in a 19-year-old African American female with extensive keloids involving her ears, neck, and pubic areas. She has been struggling with keloid disorder since she was one year old and has undergone numeorus surgeries to remove several of her keloids, with most worse after surgery.

Case Study 3

A 25-year-old African American male presented with multiple, very large tumoral keloids involving his neck (Figure 20). His struggles with keloid disorder started three years earlier when a few papular / nodular lesions developed on his neck (Figure 21). The patient’s dermatologist elected to remove these lesions surgically, yet there was a rapid recurrence, after which a second surgery was performed to remove the recurrent lesions. This time, surgery was followed by ILT injections.

Case Study 4

A 36-year-old old African American female presented with widespread keloid disorder involving numerous areas of her skin, including her neck and chest (Figure 22). She had previously undergone surgery and radiation therapy to remove multiple keloids from her neck and chest, which resulted in worsening of these keloids. She had also developed hypothyroidism after radiation therapy to her neck, for which she had been placed on life-long thyroid hormone supplement. Treating patients like this young woman at this stage of their disease is extremely challenging.

The lesson learned from this patient, and patients like her, is that surgery with or without radiation therapy is NOT a solution: it can make the condition worse and cause permanent and lifelong complications. Moreover, radiation-induced hypothyroidism is an irreversible condition requiring lifelong thyroid hormone replacement [6] and exposure to ionizing radiation is a known risk factor of thyroid cancer [7].

As for clinical management of patients like the one presented in this case study, all these patients ideally need a systemic form of treatment. It is extremely difficult to manage these patients with local treatments.

Figure 20. Case Study 3, massive neck keloids in a 25-year-old African American male.

Figure 21. Case Study 3, multiple nodular keloids in submental area three years prior to current presentation and shortly before undergoing the first surgical excision.

Figure 22. Case study 4, a 36-year-old old African American female with massive neck and chest keloids. Note that the neck keloid has merged with the superficially-spreading keloid on her chest.

Case Study 5

A 31-year-old African American male presented in May 2011 with a super-massive keloid tumor involving much of his submandibular neck skin (Figure 23). His struggles with keloid disorder started when he was only 10 years old when he first noticed a minor bump under his jaw. Over the years his disease had progressed and he had been treated with all available modalities, including five surgeries to remove his neck keloid.

All previous surgeries resulted in the worsening and progression of his disease. The last surgery was performed in 2004, and was followed with adjuvant radiation therapy. Due to the size of his neck keloid, the post resection submandibular skin defect had to be closed using a skin graft. This attempt led to the development a new keloid at the donor site on his thigh, an iatrogenic keloid (Figure 23). After all these efforts, this young man simply gave up on all further treatment.

Figure 23. Case study 5, a 31-year-old African American male with super-massive neck keloid and an iatrogenic thigh keloid that developed at the site of donor skin for the skin graft taken to cover the surgical defect created in his neck.

Unfortunately, he is not the only patient who has fallen into this vicious cycle of surgery after surgery. There are far too many patients, practically all those with massive and semimassive keloids, who have fallen onto the same path, which started with surgery to remove a small keloid lesion from their neck or another area of their skin.

Limited Role of surgery

Surgery, using a scalpel or a laser device, should never be used to remove early-stage, nodular, multi-nodular, or even semimassive tumoral neck keloids. Surgery is a known triggering factor in the formation of much larger neck keloids.

Surgery may only be considered in cases of massive neck keloids and only performed in coordination with a specialist physician who is familiar with keloid disorder and can administer proper adjuvant medical treatments, including ILC, in an attempt to prevent post-operative recurrence.

When contemplating surgery for patients with massive keloids, one has to be reminded that the lesion that is to be removed was most likely triggered by previous surgical removal of a smaller lesion.

Case Study 6

A 37-year-old African American male presented to the author in November 2015 seeking treatment for recurrent neck keloids (Figure 24). His struggles with keloid disorder started eight years earlier when he noticed small keloids on his neck. Subsequently, much like the patient presented in case study 5, this patient had also been treated with ILT and two rounds of surgery, each time followed by ILT. His keloids regrew after each surgery. Thereafter, he simply refused undergoing another surgery.

After much consideration, and with the limitations imposed by his work and his work schedule, he was started on ILC treatment with minimal response. In September 2017, almost two years after his initial presentation, he was referred for debulking surgery with the intention of aggressive post-operative adjuvant medical treatments. Figure 25 depicts the status of his neck keloids as of October 2018, approximately one year after the debulking surgery. Since his last surgery, he has been treated with ILT and ILC once every 6-8 weeks. The tumoral keloid on the left side of his face was not removed surgically due to technical issues related to approximating of the edges of the surgical wound. The patient’s work schedule has not allowed for cryotherapy to this lesion.

Figure 24. Case Study 6, Recurrent keloids along the surgical excision lines.

Figure 25. Case Study 6, one year after surgical removal of the tumoral keloids with continued post-operative adjuvant treatments with ILC and ILT.

References

- Tirgan, MH. Neck keloids: evaluation of risk factors and recommendation for keloid staging system, F1000 Research, June 28, 2016

- Tirgan, MH. Massive ear keloids: Natural history, evaluation of risk factors and recommendation for preventive measures – A retrospective case series, F1000 Research, October 13, 2016

- Miyahara H, Sato T, Yoshino K. Radiation-induced cancers of the head and neck region. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 1998;533:60-4

- Ron E. Cancer risks from medical radiation. Health Phys. 2003 Jul;85(1):47-59.

- Tirgan, MH. Laser Treatment of Keloid Lesions, Efficacy and Side Effects, Results of an on-line survey. Abstract – 2nd International Keloid Symposium, Rome, Italy June 7-8 2018. Full manuscript in press.

- Boomsma MJ, et.al. A Prospective Cohort Study on Radiation-induced Hypothyroidism: Development of an NTCP Model. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012 Nov 1;84(3):e351-6.

- Nachalon Y, Katz O, Alkan U, Shvero J, Popovtzer A. Radiation-Induced Thyroid Cancer: Gender-Related Disease Characteristics and Survival. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2016 Mar;125(3):242-6.